1877

The supervision of inmates is placed under the control of the Commissioner of Agriculture.

Florida elects Governor George Franklin Drew. The new governor found the state in deep debt from Reconstruction. Drew made the argument that prisoners should be economic assets to the state, not liabilities. He pushed for the convict lease system, and beginning in 1877, prisoners were leased to corporations and individuals to work in a myriad of industries (such as phosphate mining and turpentining). The state was paid a fee from the leasee and the leasee had to clothe, feed, house and provide medical care for the prisoner.

Governor George Drew. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

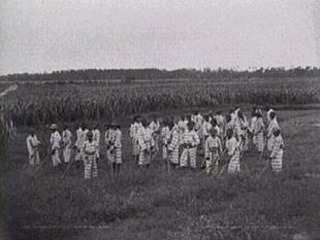

Convict leasing rebuilt southern cities and agricultural systems.

According to an article in the Panama City News Herald dated June 24, 2001 and written by Marlene Womack, conditions for these prisoners were harsh.

CONVICT LEASING SYSTEM

"Convict leasing began in 1877 when the state still faced financial hardships from the Civil War and could not afford to build more jails and prisons. The practice started slowly, then grew in acceptance near the turn of the century when just about anyone in need of workers for industries such as logging, phosphate mining, farming, railroad building, sawmilling and turpentining could lease prisoners from the state.

At first lessees paid a mere $26 per annum for each convict with the understanding that they were responsible for feeding, clothing, housing and providing medical care. When the state realized these leases were lucrative opportunities, those in charge raised the cost to $100 per annum, then $150, which still provided lessees profitable returns.

In the beginning most people favored the leasing system. They wanted criminals punished and earning their keep through forced labor. Society believed that hard work served as a deterrent against future crimes.

Those leasing prisoners also expected high returns so they employed tough bosses and guards who had the task of extracting the most labor from these convicts. Work days began at sunup and continued until sundown, six days per week.

Most of those on the outside had no idea of the high mortality rates and the brutalities that existed in some of these camps. Young men and boys from other sections of the country seemed to have the most difficulty abiding by this system of slave labor. The guards referred to them as "Yankees."

Several dishonest sheriffs and other law enforcement officials also profited from this system by providing a ready supply of prisoners, which earned them $20 per head. In some locations where the treatment could only be described as inhumane, those who lived nearby and knew the situations actually aided those who escaped from these camps.

Once convicts entered the system, they were issued numbers that sufficed for their names. As the years passed, names often became lost and only numbers remained, although a few creditable camps took photographs of their inmates.

Those trying to trace individuals usually faced difficult and often impossible tasks as thousands around the state were laid to rest in plain pine boxes beneath unmarked wooden crosses.

At most places, prisoners were shackled during the day and chained at night while they slept in stockades. In the evenings, floggings took place for those committing minor transgressions such as not performing enough work or "eyeballing" passersby on the road, instead of keeping their faces toward the ground."

Inmates gathered in the prison yard.

Inmates eat bacon, meal, flour, rice, dried beans and syrup. In the summer, they eat fresh beef once a week. In winter they eat fresh pork once a week, as well as fish. The local manager at each camp cultivates one to three acres of garden vegetables. All cells have water, and inmates are required to bathe and put on clean clothes every Sunday morning.

Inmates take a break from working.

1895

The Legislature passes a law allowing the Governor to appoint the first prison inspector at $125 per month.

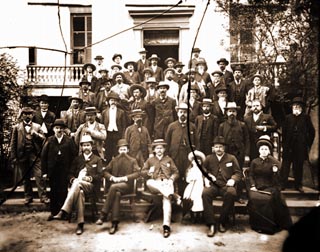

Florida legislature is photographed in 1889 sitting on the steps of the Florida Capitol in Tallahassee. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

REPORT FROM THE PRISON CHAPLAIN...

“During the year 1893, there were but four camps, and I visited them once a month. Last year there were eleven camps, and I have been getting around to them every eight weeks. I think their spiritual condition was better year before last than at present. After preaching to them, I talk to each one concerning his soul’s salvation, and think it has a good effect upon those who profess conviction.” State Prison Chaplain V.A. Herlong, in a January 3, 1895 letter to his boss, L.B. Wombwell, Commissioner of Agriculture.

- 1821-1845

- 1868-1876

- 1877-1895

- 1900-1919

- 1921

- 1922-1924

- 1927

- 1928-1931

- 1932 | CHAPMAN

- 1933-1935

- 1936-1939

- 1940-1945

- 1946-1949

- 1950-1955

- 1956-1961

- 1962 | WAINWRIGHT

- 1963-1965

- 1966-1969

- 1970-1975

- 1976-1979

- 1980-1986

- 1987 | DUGGER

- 1988-1990

- 1991 | SINGLETARY

- 1992-1995

- 1996-1998

- 1999 | MOORE

- 2000-2002

- 2003 | CROSBY

- 2004-2005

- 2006 | MCDONOUGH

- 2007

- 2008 | MCNEIL

- 2009-2010

- 2011 | BUSS

- 2011 | TUCKER

- 2012 | CREWS

- 2013-2014

- 2014 | JONES

- 2015-2018

- 2019 | INCH

- 2020-2021

- 2021 | DIXON

- 2022-Today

- Population Summary Table