1966

INMATE POPULATION JUNE 30, 1966: 7,074

Captain James Wesley Parr dies in the line of duty during an inmate escape.

DEATH OF CAPTAIN JAMES WESLEY PARR

When an officer dies in the line of duty, leaving behind a pregnant widow and three young children, it is a tragedy. In this case, the tragedy is compounded by the mysterious circumstances surrounding the officer's death, and the many questions remaining about what actually happened that day.

Captain James W. Parr

Captain James Wesley Parr, 35, died on August 11, 1966 in Pompano canal while chasing an inmate who escaped from an inmate road crew working on U.S. 441. He was a Captain at Pompano Beach Road Prison at the time. Those are the only facts in this case that are without controversy. Associate County Medical Examiner Dr. Joseph C. Rupp is quoted in the Fort Lauderdale News and Sun Sentinel the next day saying Captain Parr drowned in the canal. The reporter went on to say "It is believed Parr tried to swim across the canal and got tangled in the heavy grass and moss and drowned."

His family says this: James Parr was shot in the back, above the beltline, on his right hand side, and they have his bullet-ridden clothing to prove it. Everyone does agree that his gun was found clamped in his right hand, all bullets expended, and that he was in a kneeling position. His wife, Carolyn, said "the canal was a little over waist deep and James was an excellent swimmer. Also, according to the autopsy, his lungs were of equal weight and had no water in them."

Once authorities realized Captain Parr was missing, dozens of law enforcement officials began to search for him. He was found the next morning floating face-down in the canal, by his brother-in-law, Frank Herbert. According to Captain Parr's wife, his car was found four miles away, locked, with the keys inside it. She said the inmate who escaped that day, Murray Lawrence Sapossnek, 32, was stopped, questioned and, unfortunately, released by a Florida Highway Patrol officer miles from the canal where Parr died. His wife does not believe the inmate had anything to do with Captain Parr's death. According to Department of Corrections records, Sapossnek was recaptured on March 24, 1967 and died of a heart attack in prison on July 27, 1968. According to the Ft. Lauderdale News and Sun Sentinel article, he was in prison for forging prescriptions to obtain narcotics. Record indicate he was sentenced to two additional years for his escape.

Captain Parr had been an Army Tank Commander for the 3rd Armored Division of the Screaming Eagles and had been stationed in Ft. Knox, Kentucky and Ft. Polk, Louisiana. He worked at Pinellas Park State Prison before moving to Pompano Beach Road Prison. In his off-hours he was a lieutenant in the police reserves for the city of Ft. Lauderdale.

Captain Parr left a wife, Carolyn, and four children, Stephanie Gail, 6, Cathy Sue, 11 and James Wesley Jr., 4. Unbeknownst to Carolyn at the time, she was pregnant with their fourth child, Christopher John, who later died in a motorcycle accident. Captain Parr was honored "in one of the biggest funerals Ft. Lauderdale ever had," according to Carolyn, and is buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Broward County. A chapel at Pompano Community Correctional Center was subsequently dedicated in Captain Parr's memory.

1967

INMATE POPULATION JUNE 30, 1967: 7,339

Legislature authorizes Corrections to operate a work release program.

Also in 1967, Florida's stay of execution for inmates under sentence of death leads to a two-year moratorium on capital punishment.

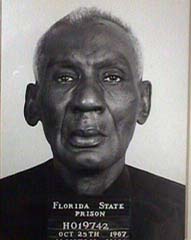

Three years after his release Clarence Martin is arrested and sentenced to one year. He begins his 8th incarceration at age 66.

|

|

On July 16, 1967 a flash fire inside the barracks used to house chain gang inmates results in the deaths of 38 men. According to a retelling of the incident in the Panama City News Herald on April 5, 1998, this is how the incident transpired.

JAY CAMP FIRE CONTRIBUTES TO END OF CHAIN GANGS

"Prisoners working the roads became a common sight in Florida and several other states. In later years, convict camps also existed in this area at places like Lake Merial and in Panama City south of 15th Street on the west side of Balboa Avenue. But on July 16, 1967, the flash inferno of a 40-by-90-foot old World War II barrack used as a stockade at Berrydale, near Jay, helped end this type of chain gang system in Florida.

According to the Pensacola Journal of July 17, 1967, 37 men burned to death in the fire. The building was a known fire hazard and was scheduled to be phased out by the state. At this camp and similar camps all over Florida, convicts were locked inside the stockade. By that time, leg irons and sweat boxes had been eliminated, but a guard still controlled inmates from behind a chain link fence or cage. The guard watched over the only entrance and held a shotgun. Inmates needed his permission to make any move. (Note: Actually 38 died, 35 in the fire and 3 later.)

The tragic incident took place during the civil rights era when racial unrest simmered around the country. The camp was composed of all black inmates until the beginning of July, when the state brought in 15 white prisoners to integrate the camp and increase its population to 51. During the first two weeks of July guards broke up two fights in the remote camp. The riot on Sunday, July 16, began about 10 p.m. when a guard took a contraband book away from Thomas E. Ard of Pensacola.

Prisoners began smashing the fluorescent light fixtures. They hurled their television set to the floor. A.O. Lovett, the guard on duty, realized the situation had gotten out of control. He ran outside and tossed the keys over the high barbed wire fence so guard Richard E. Cobb could unlock the prison arsenal for additional guns. In the meantime, Ard and Earl Hoffman, another white prisoner, and black inmate Joseph E. Wynder set fire to pieces of newspaper and toilet paper at each end of the building, possibly believing their actions would get them transferred.

When Lovett returned the fire was "tree-top high." He claimed he made four passes before he could open the stockade door due to the tremendous heat. But others told of a long delay because the guard had to go to the camp office to get the key.

Only 14 escaped the fire. Afterward 19 bodies were found huddled 4 feet high in the shower room where they sought safety. Sixteen were discovered stacked beneath a barred window. In the smoldering fire the next morning, one wall remained standing along with the steel cage, where the guard had been stationed. In Milton, the coroner's jury ruled the fire was "a criminal act of arson." Ard, Hoffman and Wynder all died in the flames."

Click here to listen to Secretary Wainwright talk about the Jay Fire.

ACTIONS OF OFFICER ARNIE LOVETT

Arnie Lovett

In the July 1967 Correctional Compass employee newsletter, then-Division of Corrections Director Louie L. Wainwright had this to say of the fire and subsequent heroic actions of FDC employee Arnie O. Lovett.

"In the tragic fire which claimed the lives of 38 inmates at Jay Road Prison on July 16, 1967, newspaper accounts commended the action of Officer Arnie O. Lovett. He was one of the men on duty when the inmates set their barracks on fire. Some of the inmates were apparently immobilized by fear as the curtain of flame separating them from the door grew nearer. Lovett went in and brought five of them out by pushing them ahead of him through the door. As a result, Officer Lovett was himself burned and later received treatment at Century Hospital. His action in the face of considerable danger is in the highest tradition of the correctional service."

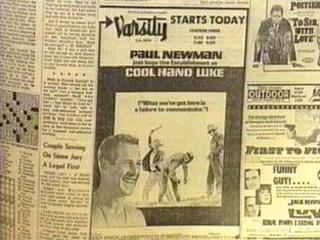

One of the most notorious Florida prison movies ever made, the Paul Newman motion picture Cool Hand Luke debuts. It is based on a book written by former Florida inmate Donn Pearce about life on a 1940s-era chain gang. Pearce makes a cameo appearance in the movie as an ex-con named Sailor. Ironically, the movie was filmed primarily in Stockton, California, not Florida. L.W. Griffith, who was the Director of the prison system's State Road Department and Prison Camps at the time, recalled that those making Cool Hand Luke filmed some exterior shots and a scene where the lead character is being chased through the woods by bloodhounds, in Florida. He said the bloodhounds were the Department's and the role of Cool Hand Luke was played by a stand-in for these shots. The filming took place at the Callahan Road Prison near Jacksonville, while the inmates were away from the facility working on the roads.

It is interesting to note that even though leg-irons like the ones featured in Cool Hand Luke were discontinued in 1945, chain gangs were reinstated for a time 50 years later.

Former Sumter C.I. Warden Clark Moody recalls some details of the making of Cool Hand Luke;

BEHIND THE SCENES OF COOL HAND LUKE

Paul Newman stars in Cool Hand Luke

"Donn Pearce served most of his sentence at the Tavares Road Prison #5758 (later #58) in Tavares, Lake County. I recall that when the book, 'Cool Hand Luke' hit the library in Tavares that there was a local minor commotion. That was around 1964-65. According to legend around the Lake County area, the role of the officer on the road gang in the movie with the mirrored sunglasses was supposed to be our State Road Department (now DOT) foreman, a man by the name of Miley, a fellow I knew very well. He had only one arm.

"What's left of the Tavares Road Prison is still where it was when Pearce was serving time, on SR19 just south of Tavares. The old office is still there, as well as the gasoline storage building and the equipment sheds. Alas, the inmate dormitory, the Bachelor's Officer's quarters, the "box", the guardstands and the grocery warehouse are all gone.

"The movie producers sent down a crew to Tavares to take pictures, make measurements, etc., before going back to the left coast and replicating the movie set prison there. Fred Hale was the Captain at #58 during that period and he and I discussed it at a meeting in Ft Lauderdale in the middle or late 1960s. When the pictures were taken and measurements made, the road prison was still being operated. The movie set was very close to the original. I went by the site of #58 a few years ago and the desk that I used in 1962 was STILL THERE, and a list of telephone numbers in my handwriting was still on the slide out."

Warden Clark Moody

Newspaper advertisement for "Cool Hand Luke"

The movie was based on the novel by

Florida Inmate Donn Pearce.

The 1940s-era movie was filled with scenes similar to this 1940s photo of a correctional officer supervising a Florida chain gang.

1940s photo of inmates working in a "Chain Gang."

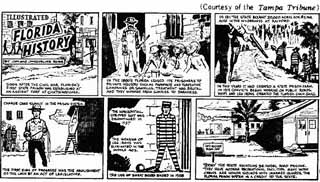

This 1967 Cartoon from the Correctional Compass shows a brief overview of the history of corrections in Florida and concludes with "Today the state maintains 34 model road prisons. They have modern recreational facilities. Many work crews are honor squads with unarmed guards. The Florida prison system is a credit to the state." Click for larger view.

This joke was included in the March 1967 edition of the Correctional Compass, the Department of Corrections newsletter, to illustrate a point about "passing the buck."

1960S HUMOR

A preacher once called the sheriff of his county and reported that there was a dead donkey near his church and asked if he would see that it was taken care of in the proper manner. The sheriff replied that he had always understood that it was a responsibility of clergy to lay away the dead. The preacher responded by saying that while he had no disagreement with the statement, it was also the duty of the clergy to notify the next of kin.

- 1821-1845

- 1868-1876

- 1877-1895

- 1900-1919

- 1921

- 1922-1924

- 1927

- 1928-1931

- 1932 | CHAPMAN

- 1933-1935

- 1936-1939

- 1940-1945

- 1946-1949

- 1950-1955

- 1956-1961

- 1962 | WAINWRIGHT

- 1963-1965

- 1966-1969

- 1970-1975

- 1976-1979

- 1980-1986

- 1987 | DUGGER

- 1988-1990

- 1991 | SINGLETARY

- 1992-1995

- 1996-1998

- 1999 | MOORE

- 2000-2002

- 2003 | CROSBY

- 2004-2005

- 2006 | MCDONOUGH

- 2007

- 2008 | MCNEIL

- 2009-2010

- 2011 | BUSS

- 2011 | TUCKER

- 2012 | CREWS

- 2013-2014

- 2014 | JONES

- 2015-2018

- 2019 | INCH

- 2020-2021

- 2021 | DIXON

- 2022-Today

- Population Summary Table