1933

INMATE POPULATION DECEMBER 31, 1933: 3,144

Giuseppe Zangara attempts to assassinate President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt in Miami's Bayfront Park. Instead, he mortally wounds Chicago mayor Anton J. Cermak. In perhaps one of the shortest periods of time between crime and execution (32 days), Zangara is executed on March 20, 1933 in Florida's electric chair. The bizarre story of Zangara is detailed in a book by Blaise Picchi entitled "The Five Weeks of Giuseppe Zangara: The Man Who Would Assassinate FDR."

Giuseppe Zangara killed the Chicago mayor and attempted to assassinate Franklin Roosevelt.

The following is an excerpt from a review of that book, written by Florence King.

WRITTEN BY FLORENCE KING

"At 9:15 on the evening of February 15, 1933, the greatest "what if" in American history was played out in Miami's Bayfront Park. The attempted assassination of President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt is almost forgotten today, but for connoisseurs of Fate there is nothing quite like it.

FDR arrived at the political rally tanned and relaxed from a deep-sea fishing trip on Vincent Astor's yacht. Sitting atop the back seat of a convertible, he rode slowly through the packed crowds and stopped in front of a stage full of VIPs, among them the mayor of Chicago, Anton J. Cermak. After making a brief speech from the car, he was talking privately with the dignitaries who came down from the stage to greet him when five shots rang out.

Some 30 feet from the car, a man in the third row of spectators was standing on tiptoe on a rickety chair, his arm stretched over the heads in front of him, firing a .32 revolver at the presidential party. Directly behind him was Thomas Armour, a Miami carpenter. Directly in front of him was Mrs. Lillian Cross, wife of a Miami doctor, who was also standing on a chair. Either Armour or Mrs. Cross grabbed the gunman's arm to deflect his aim -- both so claimed afterwards -- or perhaps it was the unsteady chair. Whatever happened, all five shots missed FDR and hit others. Two people were seriously wounded: a Mrs. Mabel Gill and Mayor Cermak.

The crowd and the police pounced on the gunman. The Secret Service ordered FDR's driver to get out of the park but the president-elect countermanded them and went back to pick up the wounded. On the way to the hospital he cradled Anton Cermak's head on his shoulder and kept talking to him -- "Tony, keep quiet, don't move, Tony" -- a steady murmur of encouragement that doctors later said kept Cermak from going into shock.

FDR stayed four hours at the hospital, showing by his actions what he would soon express in words about the need to banish fear. That his behavior this night was fresh in the minds of the nation that heard his First Inaugural address established his presidential bona fides as no mere speech could: The people around FDR were watching him to see how this man who was about to lead a troubled nation would react to the attempt on his life. That February evening he was still an unknown quantity. In the immediate aftermath of the assassination attempt, virtually every word and action of the president-elect was reported to the nation.... Was he frightened? Nervous? Relieved that he had escaped unhurt? Was he rattled or petulant? He was none of those things. He appeared unfazed, calm, deliberate, cheerful -- throughout the shooting itself as well as during its aftermath. He said and did all the right things at the right times: He stopped the car twice to pick up the wounded; he assured the crowd that he was all right; he calmly talked Cermak out of shock, and he visited the victims that night and returned to the hospital the next day with flowers, cards, and baskets of fruit. He had met his first test under fire, and he had impressed not only his associates, but the press and the nation. It was on this note of personal courage, graciousness, and self-confidence that he was to assume the reins of government seventeen days later.

The gunman was a naturalized Italian bricklayer named Giuseppe Zangara who stood all of five-foot-one, hence his awkward firing position. He may be our most interesting assassin, if only because he was a registered Republican whose chief motivation seems to have been hypochondria. Born in 1900 in Calabria, the province at the toe of the boot, he was a sickly child made sicker by a brutal father who beat him, starved him, and put him to work at the age of six, when his chronic stomach pain began. This pain became the central fact of his life. He brought it up constantly during his questioning, interjecting it into his simplistic political views: "I shoot kings and presidents, capitalists got all-a money and I got bellyache all-a time."

He sounded like an anarchist, yet he condemned them along with Communists, Socialists, and Fascists, proudly insisting that his views were "nobody but mine," a claim borne out by a search of his room. Unlike the Oswalds of this world he had no taste for turgid political manifestos; the few books he owned were English-language aids.

Walter Winchell, who was in Miami that night, immediately concluded that Zangara was not a presidential assassin but a hit man for the Chicago mob who had been sent to shoot the man he did in fact shoot: Mayor Anton Cermak. Many people agreed; Cermak was a reform mayor and dedicated anti-Prohibitionist who had made enemies in the underworld, but Zangara insisted that he wanted to shoot only "kings and presidents" and disclaimed all ties to all groups except the bricklayers' union, which, he said, he had joined only because he had to. "I don't like no peoples," he explained.

The FBI investigation proved him right: He belonged to nothing and no one. An atheist, he believed only in "what I see. Land, sky, moon," and said he felt no remorse over wounding Cermak and Mrs. Gill, but his rationale was not so much cold and psychopathic as matter-of-fact and practical: "You can't find a king or a president alone. Lots of people stick around him and you got to take chance to kill him. All the chiefs of people, never alone. The chief of government you no see alone. He go all the time with a bunch."

Since Cermak and Mrs. Gill were still alive, Zangara was arraigned on four counts of assault with intent to kill, with a murder charge pending should one or both of them die. He insisted on pleading guilty, saying, "I kill capitalists because they kill me, stomach like drunk man. No point living. Give me electric chair." Sentenced to four terms of 20 years each, he told the judge, "Don't be stingy, give me hundred." He rejected an appeal.

The whole picture changed for Zangara when Anton Cermak died on March 6, two days after FDR's inauguration. His death came about through a misdiagnosis of his injuries that his doctors tried to cover up by citing a pre-existing condition. This opened a legal door for Zangara to claim that his bullet had not caused Cermak's death, but he insisted on pleading guilty.

He was electrocuted on March 20 in what still stands as the swiftest legal execution in this century. It's a measure of his unknowable personality that he was able to be both stoic and cocky in the death chamber. To the minister intoning sonorous prayers he snapped, "Get to hell out of here, you sonofabitch," and strode toward the chair unassisted, shouting, "I go sit down all by myself." A reporter-witness compared it to a man hopping into a barber's chair. As they put the hood on him he called out, "Viva Italia! Goodbye to all poor peoples everywhere!" His last words, spoken to Sheriff Hardie at the controls, were "Pusha da button!"

The story of the attempt on FDR's life has never been told except in a few magazine articles, but now Florida criminal lawyer Blaise Picchi has filled the 65-year gap with The Five Weeks of Giuseppe Zangara, a book that is impossible to put down. A native Floridian, Picchi paints an evocative picture of a vanished Miami that conveys the texture of a bygone age, interviews the still-living persons who were there on the fatal night, digs up never-published documents, and presents a Zangara who is intriguingly reminiscent of Celine, the French writer who was cleared of charges that he collaborated with the Nazis when the judges agreed that "he was too much of a loner to collaborate with anybody."

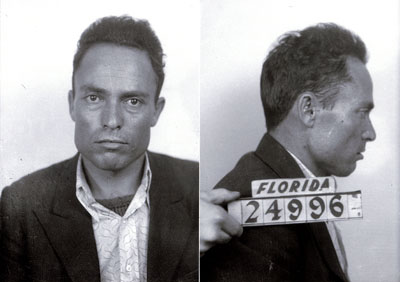

Zangara was put to death in the electric chair on March 20, 1933. After swearing at the witnesses because no cameramen were there to take photographs, he said "Push the button. Go on and push the button." (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

Giuseppe Zangara in custody after his unsuccessful attempt on President Roosevelt’s life. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

The following is from a letter written by B.H. Dickson, Supervisor of State Convicts, to the Honorable Nathan Mayo, Commissioner of Agriculture dated February 8, 1933, Tallahassee, Florida (from the Twenty-Second Biennial Report of the Prison Division of the Department of Agriculture of the State of Florida for the years 1931 and 1932).

LETTER FROM DICKSON TO MAYO, FEBRUARY 1933

Suggesting Classification of Inmates...

"...I wish again to call attention to a matter which was contained in my former report, to-wit: That is the recommendation that prisoners of bad character, commonly called incorrigibles, be placed in camps separate and apart from the ordinary prisoners. The influence of the few incorrigibles upon the temper of a large body of ordinary good prisoners is bad, and these unruly ones should be segregated and placed in separate camps where they may be dealt with as their character and temperaments require, and where their evil influence may not work upon the discipline of good prisoners."

Today, inmates who consistently disobey prison rules and create disturbances in the facilities are placed in separate confinement areas, or Long-Term Restricted Housing or Administrative Management Units (AMUs), which were created to separate predatory, disruptive and potentially violent inmates so they can’t prey on vulnerable inmates in the general population, just as Mr. Dickson suggested decades ago.

The following is from a letter written by the Honorable Nathan Mayo, Commissioner of Agriculture to the Honorable David Sholtz, Governor of Florida, dated February 15, 1933, Tallahassee, Florida (from the Twenty-Second Biennial Report of the Prison Division of the Department of Agriculture of the State of Florida for the years 1931 and 1932).

LETTER FROM MAYO TO THE GOVERNOR, FEBRUARY 1933

Uniformity in when sentences begin suggested...

"...I recommend a law providing that all commitments to State Prison be made uniform. That is, that the courts be required to stipulate in their sentences whether sentence begins the date passed or the date received at State Prison. Under our present system, it frequently happens that prisoners sent up on the same date, for a like offence (sic), and receiving the same term of sentence, some are made to serve 3 to 15 days longer than others. This, in my opinion, is a discrimination, and should be remedied by law."

This issue is corrected in 1963 when Florida Statute 921.161 was enacted. This statute states that an inmate is to receive credit for the time served between date of sentence and delivery to the state prison. Sentencing Guidelines, which address uniformity in the length of sentences for similar crimes, were not implemented for another 50 years (October 1983).

Raiford Women's Ward 1933. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

Raiford prison entrance in 1934. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

Aerial view of the main housing unit at Raiford in 1933. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

- 1821-1845

- 1868-1876

- 1877-1895

- 1900-1919

- 1921

- 1922-1924

- 1927

- 1928-1931

- 1932 | CHAPMAN

- 1933-1935

- 1936-1939

- 1940-1945

- 1946-1949

- 1950-1955

- 1956-1961

- 1962 | WAINWRIGHT

- 1963-1965

- 1966-1969

- 1970-1975

- 1976-1979

- 1980-1986

- 1987 | DUGGER

- 1988-1990

- 1991 | SINGLETARY

- 1992-1995

- 1996-1998

- 1999 | MOORE

- 2000-2002

- 2003 | CROSBY

- 2004-2005

- 2006 | MCDONOUGH

- 2007

- 2008 | MCNEIL

- 2009-2010

- 2011 | BUSS

- 2011 | TUCKER

- 2012 | CREWS

- 2013-2014

- 2014 | JONES

- 2015-2018

- 2019 | INCH

- 2020-2021

- 2021 | DIXON

- 2022-Today

- Population Summary Table