1963

INMATE POPULATION JUNE 30, 1963: 7,597

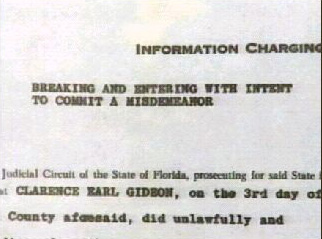

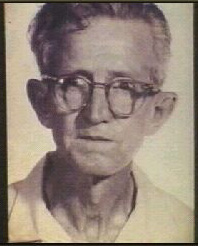

The landmark court decision in the Gideon vs. Wainwright case leads to the right to free legal counsel for anyone charged with a felony. Fifty-one-year-old Clarence Gideon was charged and convicted of breaking and entering a pool hall. He was sentenced to prison without help from a lawyer. He filed an appeal and was retried. With the help of counsel, he was acquitted.

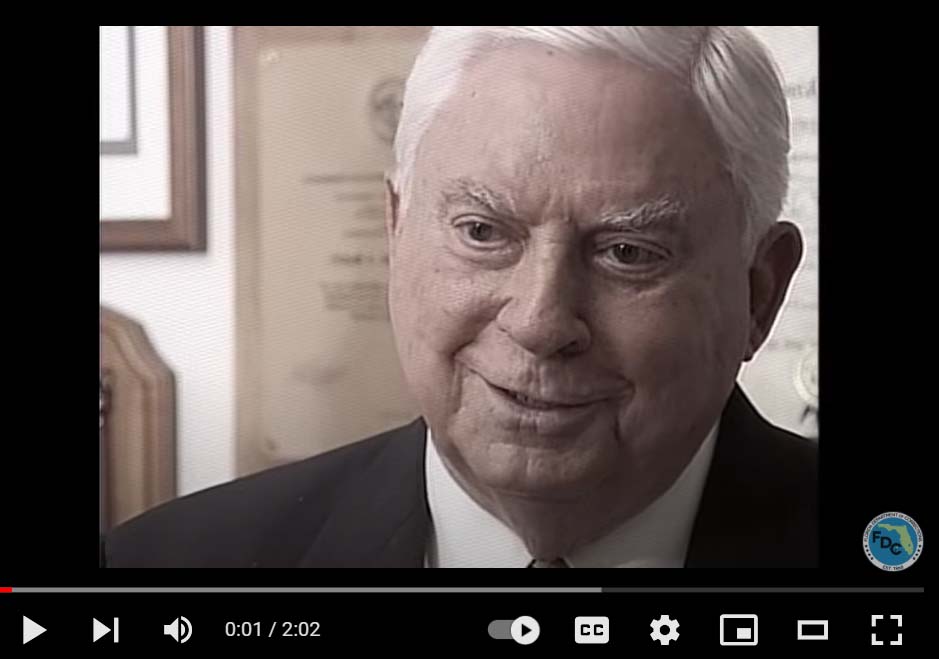

Clarence Gideon

Click here to listen to Secretary Wainwright talk about releasing inmates early and how it relates to the Gideon case.

1964

INMATE POPULATION JUNE 30, 1964: 6,746

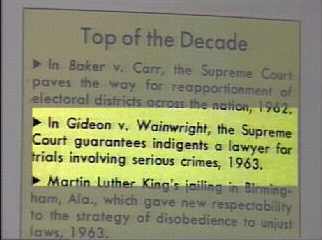

"Gideon's Trumpet," a book written by Anthony Lewis detailing the Gideon case, is published and made into a movie. Time Magazine states that Gideon vs. Wainwright is one of the 10 most important legal events of the 1960s.

Time Magazine covers the Gideon vs. Wainwright story

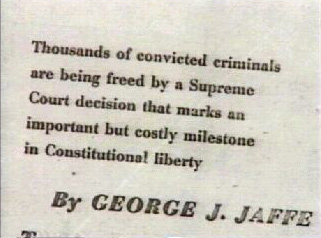

Inside Time Magazine

The case is one of the most important events of the decade.

Quote by George J. Jaffe

Gideon's Charging Papers

Gideon's letter changed American Law

Gideon's Trumpet was written several years later detailing Gideon's situation.

Robert F. Kennedy noted that if Gideon hadn't written the letter, the "vast machinery of American Law would have gone on functioning undisturbed."

ODDITIES IN THE NEWS

Correctional Compass, July 1967

In 1964, inmates digging the foundation for the Apalachee Correctional Institution Administration Building found the fossilized remains of a manatee that lived 20-30 million years ago, according to state paleontologists.

1965

INMATE POPULATION JUNE 30, 1965: 76,970

Sumter Correctional Institution located at Bushnell opens.

Lester B. Sumner, a foreman supervising inmates for Fort Myers Road Prison, was killed by three inmates during their escape on April 26, 1965.

One deer with a fatally bad sense of direction almost changed the course of corrections history on a cool January night in 1965. Paul A. Skelton, Jr., then-Deputy Director for Business Affairs, recalls what happened in his own words...

DEERLY-DEPARTED ALMOST CHANGED CORRECTIONS HISTORY

by Paul A. Skelton, Jr.

On January 19, 1965, Louie L. Wainwright, Director of the Division of Corrections, accompanied by Mrs. Wainwright, David D. Bachman, Deputy Director for Inmate Treatment and me (then Deputy Director for Business Affairs) flew to Avon Park Correctional Institution in the State Board of Conservation Plane (Cessna 310) No. N172V, piloted by Lieutenant Commander W. C. Wainright. The purpose of the trip was to participate in a panel discussion arranged by D. R. Hassfurder, Superintendent of Avon Park Correctional Institution and APCI's Education Department.

The program was concluded at 7:30 p.m. and we proceeded to the landing strip of the Avon Park Bombing Range. After final checkout of the plane and engines, the flight took off at 8:00 p.m. The plane had reached a ground speed of approximately 90-mph when there was a terrific explosion immediately under the right-hand side of the cockpit. Needless to say, there were a few anxious moments at this point, for only the pilot and Director Wainwright had seen the cause of the explosion. A 90-pound doe deer had been hit by the right hand side of the landing gear, thus preventing complete retraction. The pilot made an effort to pull the plane up when he saw the deer jump, but there was not sufficient time. Great credit goes to Lieutenant Commander Wainright for getting the aircraft airborne after impact.

The plane was navigable and the decision was made to change the flight plan from Tallahassee to Tampa, knowing that facilities for emergency landing were more readily available there than in Tallahassee. At this point, the pilot was uncertain as to whether or not the landing gear could be lowered manually and we hoped the Tampa airport tower could visually examine the underpinning of the aircraft and assure us that the wheels were completely down. The Tampa airport tower requested that we fly by as low and as close as possible to the tower and they would try to examine the aircraft. Because it was dark, it was difficult to examine the plane through field glasses, and the tower could give no assurance as to the condition of the landing gear. After four times over Tampa International Airport at 150 feet, those of us on the plane were still surprisingly composed!

The tower then suggested we fly over the runway high intensity approach lights of the Tampa Airport to permit a ground observer to see if he could determine the condition of the landing apparatus. We then flew four additional times over the lights in order to give the ground observer an opportunity to advise whether or not he felt the landing gear would be safe to use. It became apparent after the fourth pass that we would be unable to receive any assurance from the Tampa Airport officials that it would be safe to use the landing gear of the plane. The tower operator advised the pilot that MacDill Air Force Base had offered its facilities if we had an emergency and to switch over to the MacDill Air Force Base radio frequency for direct conversation with the tower at the Air Base. The tower at the Air Base advised that the General had offered the facilities of MacDill Air Force Base if such were necessary. Pilot W. C. Wainright advised the tower that it was an emergency and requested permission to use the facilities of the airfield. The tower then advised that it would be necessary for the Air Base to recover 16 jets that were in the air and it would be approximately one hour before we could make the emergency landing. The decision then was made to fly over Tampa Bay for the hour that would be necessary before the emergency landing could be made. This we proceeded to do. There was very little conversation during this hour, as you might imagine.

Approximately 55 minutes after the tower advised that it would be an hour before we could make the emergency landing, we were advised by MacDill Air Force Base that the Air Force was ready to accept the aircraft. We were informed that the General had made all emergency arrangements such as having ambulances, doctors, nurses and fire fighting equipment on the scene. The airstrip had been foamed for 2,400 feet and the tower requested that we fly over the strip to determine the location of the foam. We were told that the General would have his personal car at the beginning of the foam and we should get lined up with his vehicle. The pilot circled the airstrip and came in very low over the landing place to become oriented as to the location of the foam. While the foam was twenty feet wide, it was very difficult to see from the air, particularly at night. Two low-level passes were made over the airfield and the General advised that he felt it would be well for us to come in on the third go around, since the foam would disappear if we delayed much longer. We advised the airfield that we would be coming in on the next pass and the General moved his car out of the way, since we had become oriented as to the location of the foam. The pilot made a beautiful approach to the foam and put the aircraft down into the middle of the cover. It seemed to all of us in the aircraft that we would never reach a stopping place, however, there was no bounce at any time and the grinding of metal was just like you've heard in the movies.

The tower had advised us that we would be protected at all times by helicopters that would immediately fly over the aircraft upon descent if there was a fire. When we alighted from the aircraft after it came to a stop, which conveniently was outside of the foam, we noticed three helicopters flying immediately over the aircraft and also numerous fire trucks and asbestos-clad firemen already at the airplane with hose nozzles in hand, ready to douse any potential fire. We were greeted by doctors and nurses, as well as the Commanding General of MacDill Air Force Base and his staff. Also on hand was a Catholic Chaplain who asked if there was anything that he could assist us with. Everyone was so glad to be back on the ground that we were at a loss as to what could be done at that time. The time was 11:15 p.m. Three hours and fifteen minutes had elapsed since impact with the deer.

As a result of the skillful maneuvering of the aircraft, the Pilot, W. C. Wainright, was recognized at a Cabinet Meeting through adoption of an appropriate resolution commending him on the care and skill with which he maneuvered the aircraft to a safe landing.

Pictured (l to r) at the E. R. Cass Awards ceremony in 1983 are winners John J. Moran, Amos E. Reed and Paul A. Skelton, Jr. It's interesting to note that two of the individuals on the plane that day received the E. R. Cass Award from the American Correctional Association, which is given to individuals who are considered corrections' most dedicated professionals: Louie L. Wainwright (1976) and Paul A. Skelton, Jr. (1983). In addition, several other former or current Department of Corrections employees will earn this award over the years: former Florida Dept. of Corrections Accreditation Manager C. Winston Tanksley (1984), former Secretary of the Department of Corrections Harry K. Singletary, Jr. (1992), former Regional Director Lee Roy Black, Ph.D. (1996), former warden Anabel P. Mitchell (2000), former Secretary Mark Inch (2013), and former Director of Mental Health Services Dean Aufderheide (2021).

- 1821-1845

- 1868-1876

- 1877-1895

- 1900-1919

- 1921

- 1922-1924

- 1927

- 1928-1931

- 1932 | CHAPMAN

- 1933-1935

- 1936-1939

- 1940-1945

- 1946-1949

- 1950-1955

- 1956-1961

- 1962 | WAINWRIGHT

- 1963-1965

- 1966-1969

- 1970-1975

- 1976-1979

- 1980-1986

- 1987 | DUGGER

- 1988-1990

- 1991 | SINGLETARY

- 1992-1995

- 1996-1998

- 1999 | MOORE

- 2000-2002

- 2003 | CROSBY

- 2004-2005

- 2006 | MCDONOUGH

- 2007

- 2008 | MCNEIL

- 2009-2010

- 2011 | BUSS

- 2011 | TUCKER

- 2012 | CREWS

- 2013-2014

- 2014 | JONES

- 2015-2018

- 2019 | INCH

- 2020-2021

- 2021 | DIXON

- 2022-Today

- Population Summary Table