Early discipline included devices like the barrel restraint. (Photo courtesy of FPC.)

THE WOODEN BARREL

The next day Courson decided to break Maillefert's spirit once and for all. He ordered him to strip, then forced the unclothed prisoner into a 50-pound wooden barrel which he attached by hammering pieces of wood around his neck and tying on leather straps. When Maillefert complained that the fastenings were too tight, Courson replied that he didn't "give a damn." That day Maillefert spent most of the time sitting on a piece of U-shaped pipe in the yard. The pipe was the only place he could find that allowed him to see by craning his neck over the edge of the barrel.

Without clothing, Maillefert's badly bruised body became ravaged by flies, mosquitoes and gnats, causing numerous bumps and sores. Maillefert asked for food but received none. Guards lodged the barreled man in the cramped sweat box that night.

The next morning when a guard opened the door, prisoner E.L. Smith said Maillefert fell and because of the barrel rolled on the ground. Courson and some of the others broke out laughing. One remarked that he looked like an overturned turtle in the sand, trying to right itself. But Maillefert finally made it to his feet.

THE ATTEMPTED ESCAPE

That afternoon while no one was paying attention to him, Maillefert began gnawing on his straps and broke loose. He grabbed an old piece of blanket as cover and ran into the woods, trying to escape Courson's persecution. But Jersey's freedom lasted only a short time. Higginbotham, some of the trustees and the bloodhounds soon caught up with him. The guard wanted to kill Maillefert on the spot, but a truck driver by the name of John Mathews, who witnessed the capture, stopped him.

When they all arrived back in the camp yard, Higginbotham pulled Jersey off the truck. He fell and a puppy he had befriended began licking his face.

Courson then made one last attempt to break Maillefert, according to Smith's testimony. He nailed illegal 17-pound stocks around his feet, then wrapped a trace chain around his neck.

As Maillefert hobbled back into the sweat box, Higginbotham attached the chain to the rafters. Maillefert asked for a drink of water and took a couple of swallows. Higginbotham snatched it from him and said, according to testimony, "if you can still drink, that damn chain's not tight enough." Then, as some of the prisoners watched, Higginbotham pulled the chain so taut the weakened Maillefert could not reach the floor if he collapsed. When one of them asked Courson how long he intended to keep Jersey in that position, he was said to have replied "till Christmas or until he's dead. I intend to get his damned mind right."

Maillefert told some that he knew he could not endure this punishment. He was too weak from lack of food and the beatings to be able to stand all night. Smith testified that in leaving, he heard Courson say in a low voice, "it won't be long," as they all walked to the mess hall for supper. Forty-five minutes later when they returned, a trustee checked on the prisoner and found him ashen and not breathing. The trustee and others quickly released Jersey. They tried to revive him for half an hour. But all efforts failed.

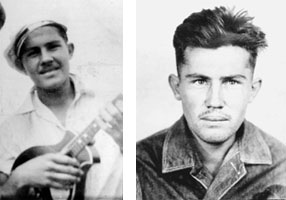

While the men worked on resuscitation, Courson was said to have come up with the story that Maillefert hung himself, according to several of the men. He ordered all of them to back his story. Tyler pronounced Jersey dead before he was carried to the mess hall so the encrusted sand could be washed from his body. Under orders that he protested, Higginbotham dressed Maillefert in his own suit and also supplied undergarments, his white shirt and a tie. Once Jersey was clothed, Higginbotham reportedly said, "he favors me."

At the opening of the second week, the judge ordered three sessions per day, one in the morning, afternoon and evening. By then threats had been made against the defense attorneys and the judge. Embalmer V.C. Wisner from the nearby Conant Funeral Home testified that the convict's body was "so badly bruised that separate bruises would be hard to describe."

COURSON AND HIGGINBOTHAM TESTIFY

The two defendants were the last to testify. With tears in his eyes, Courson spoke a long time about the way he made every effort to help the incorrigible boy. He claimed that he would have removed Maillefert from the box if he promised to do right, but the young man would never say those words. As to starving him, Courson said that he would have provided Maillefert his own meal if he had just asked for it.

But when the big question was asked by Durrance as to why he did not return Maillefert to the State Prison Farm once he experienced trouble with him, Courson replied that he was "powerless to do so with all the red tape."

Although 80 witnesses were summoned for the trial about 33 were called. Some of the convicts defended the camp captain, but several others presented a more lurid picture. They admitted they had seen men whipped, but none received the licking and floggings that Maillefert did.

THE VERDICT

On Oct. 15, 1932, after the 12-man jury deliberated two hours, they brought in a verdict of manslaughter against Courson, but acquittal for Higginbotham. Mrs. Courson began weeping while Mrs. Maillefert remained dry eyed and stared at the floor. Avriett said that he would immediately seek a new trial.

The Maillefert case became the basis for a motion picture. After the convict's death, improvements were made to the Sunbeam sweat box. Black convicts replaced the white prisoners at Sunbeam road camp.

MARLENE WOMACK, Contributing Writer. (The last of two articles on Florida's early penal system.) http://www.newsherald.com/archives/article.display.php?id=48787. For additional information, see also the July 12, 1998 story in the Florida Times-Union.